“A small crowd of people gathers at the beginning of the trail. It’s two in the morning. The moon that decided to stay hidden behind the clouds gives space for absolute darkness to reign. The group seems apprehensive and focused. Individually everyone checks their equipment: flashlight, water bottle, and mask.”

This is the first paragraph of an article I wrote 4 months ago (30/03/2020). It was forgotten on my computer because after I wrote it, the coronavirus that was until then concentrated only in Wuhan, spread across the world.

Because of that, my story lost importance in the face of something so insane, but it gained strength again when I received the information that the trail to the Ijen Volcano, in Java, Indonesia, reopened last saturday.

I thought it was worth picking up where I left off and sharing this experience.

Ps. My plans were to publish this story specifically in a newspaper and a magazine, but when it was not possible, I shelved everything I did, promising myself to share it on my own in the future. And here I am two years later.

At the end of the article you can see the full photo gallery.

Indonésia, February 29, 2020

[…]

I tried to sleep the night before, but as soon as I closed my eyes, I felt something slowly eat away at my stomach. It is not every day that you make a night trail into an active volcano.

Anxiety took my sleep the night before, but what I saw and felt inside the crater of the Ijen volcano in Java also prevented me from sleeping properly for the next two nights.

The steep climb makes a man next to me gasp. I counted only ten steps before I heard the first blast of air come out of his lungs.

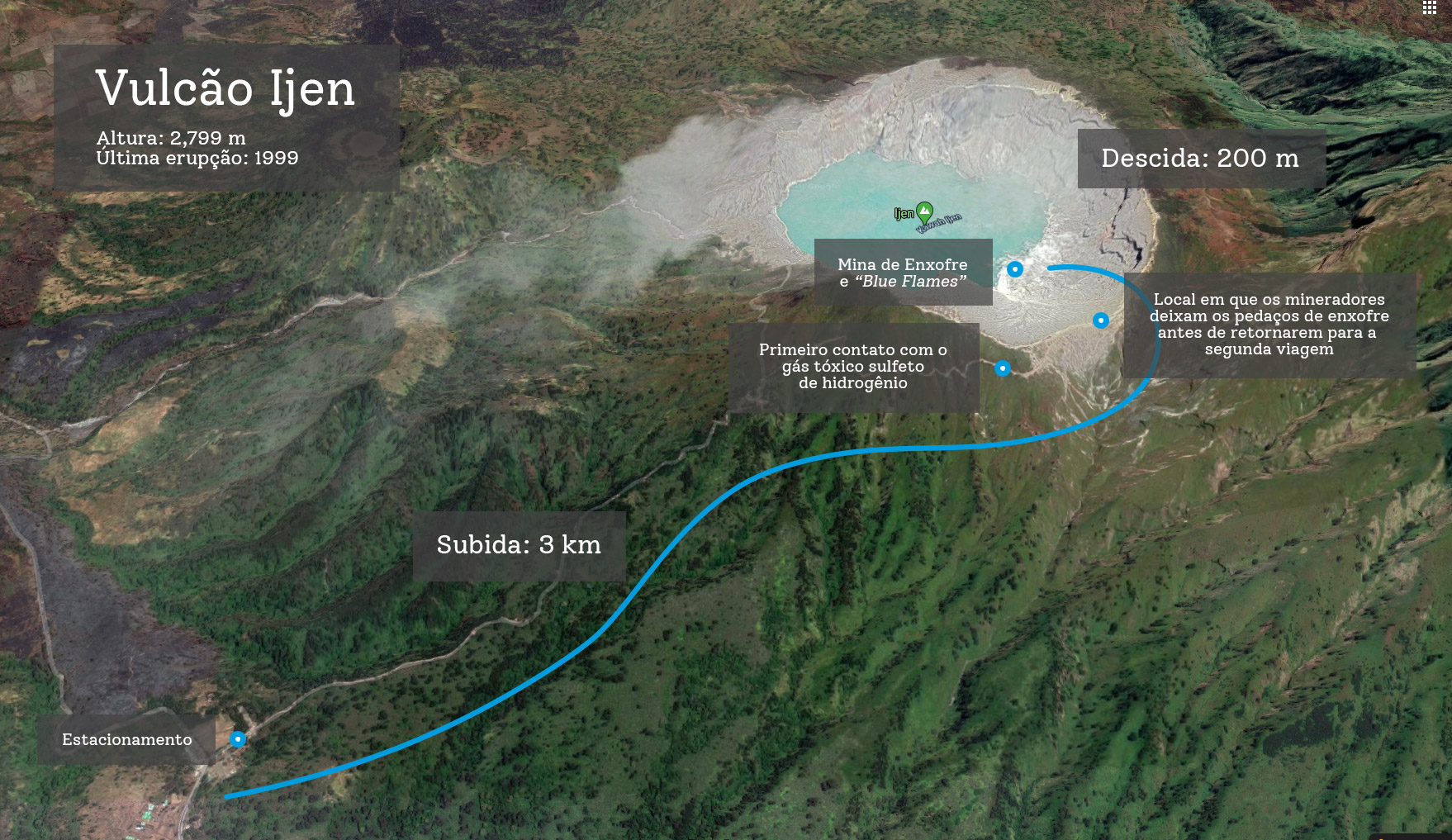

The groups distance themselves. Me, Dion – the guide who accompanies me – and his flashlight, are embraced by the pitch dark. The almost three kilometers of uphill are arduous and intense. Our boots roll the small gravel pebbles that cover the floor. At each step, the heart takes an express train to the mouth and returns.

The climb finally ends and we start walking through a flat area. But without time to catch our breath, we are hit by smoke in the form of a punch. A rotten, aggressive smell enters the nose and lodges in the throat. It’s almost three minutes of coughing.

It’s time to put on the mask to protect ourselves from the gas expelled from the mountain and head towards the crater, the heart of the volcano, 200 meters below where we are.

I had decided to hike Kawah Ijen the week before. I planned to ride a motorcycle trip around the island of Bali when I came across a photo of this place. A paradise blueish-greenish lake in the middle of a volcano’s crater. I had never gone up one and saw in the situation a unique opportunity.

The trail starts at night because inside the crater it is possible to see what they call “blue flames”. A natural effect generated by the gas that produces sulfur, hydrogen sulfide gas. The shock of the gas at a temperature between 400 and 600 degrees Celsius with oxygen from the atmosphere, creates the combustion that originates the flames. When it is dark it is possible to see several traces of that blue fire going down the slope of the volcano.

My trail-related research was simple. As I had seen pictures of tourists, I focused only on finding companies that did the tour. The descriptions on the websites were simple and generic. They showed the “blue flames”, the lake, the yellow sulfur stones and said that the mask to protect against the gas was included in the package. This only made me find the tour even more exciting.

However, there is something they don’t talk about, or that is too much between the lines. Something that when it started to reveal itself to me, made my observations blend even more deeply with my feelings.

In this crater, there is a sulfur mine still in operation.

It’s three-thirty in the morning and we’re ready to go down the last 200 meters. It is difficult to breathe using the mask. Dion explains to me that the priority on the route is to give space, both on the descent and the ascent, to the miners. I feel confused. We started walking towards the crater. With one hand I hold the cell phone that I use as a flashlight, while the other hand continues to feel the rocks along the way. This is the most difficult section of the trail. An extremely steep and slippery stone path. It is sometimes possible to see cliffs on both sides. How come there are miners who make this track in the middle of the night?

The sulfur mine was opened in 68 and is one of the last in this style still in operation. The beautiful blueish lake has levels of acidity capable of dissolving clothes and corroding metal. It is the largest acid lake in the world. And if you add to the equation that we are inside an active volcano, it turns Kawah Ijen into one of the most toxic and dangerous places on the planet.

Many tourists travel there precisely because they know it. But others have no idea what they’re getting into. I was one of those.

As soon as we arrive at our destination, we are warmly welcomed by yet another cloud of gas. It was waiting for us like a dog waiting for its owner after a full day of work. However, in this case, the animal is more like a hyena. As we are wearing masks, the smell of the corpse is not so strong, but now it is the eyes that feel the sting and start to water.

Several tourists line up as soon as they see the blue flames. Everyone pulls out their cell phones faster than gunmen in a western movie.

It is dark and the flames dance with each other. It is magnificent.

As more tourists arrive, the lanterns’ light locks hit the place. I identify several pipes going down the slope. I don’t understand anything again. I was only able to understand all this clearly when I did my research work two days later. I discovered that these pipes bring the gases from inside the volcano. The drastic change in temperature not only causes combustion but also helps in the condensation process. An orange liquid drips from the end of the pipes, forming several puddles. When this liquid hardens, the work of the miners begins.

I look to the side, and through the lighted clouds, I see a miner holding an iron spear in both hands. He raises his arms, stands on tiptoes and brutally hits the yellow floor. The place splits. He perfectly repeats the movement three more times.

As soon as it ends, two other miners emerge and begin to remove large sulfur chunks from the region with their own hands. They organize the yellow stones in straw baskets that are close to the site.

This sulfur is sold to several industries and used mainly to whiten sugar, make cosmetics and fertilizers.

The discomfort adds to an unexpected excitement, and they fight a battle inside me.

The excitement is because I worked for years as a photojournalist in Brazilian newspapers. And this type of dangerous situation causes adrenaline that spread throughout the body. The movements are agile, the eyes map the whole situation and the brain makes connections between information that, seconds before, would pass by.

In the blink of an eye, I am on the side of the miners, all their work happens closer to the pipes that spit out toxic smoke. Most of the miners I see wearing masks, but some protect themselves only with pieces of cloth. None of them are wearing gloves or glasses.

Another smoke hits me, but this one is much denser than the others. It is as if the heat wanted to melt my body. I squat down and even wearing a mask, I started coughing hard. Miners also cough, but they don’t stop working.

I went from heaven to hell in just 200 meters.

Ijen volcano workers have one of the most dangerous professions in the world. The level of hydrogen sulfide gas in this location is 40 times higher than any safety limit. The two baskets containing the sulfur pieces weigh up to 90 kg. They carry the baskets on their backs to the top of the crater and then descend with them to the base of the volcano. Miners make up to two trips a day and earn about five dollars a trip. These miners’ wages are considered to be one of the best in eastern Java.

Working in the sulfur mine exponentially shortens the life of these workers. Many have come from the countryside and are taking chances to provide a better life for their families and education for their children.

Within this scenario, tourists inspire high concentrations of toxic gases while taking pictures, posing with miners and pretending to carry baskets of sulfur on their shoulders. On Youtube, it is possible to see several “influencers” who lived this experience and filmed these workers in the same way as people photograph animals in a zoo.

I walk away from the smoke, cross a wooden bridge and watch the whole scene from afar. I think of my role within that environment. I reflect on what I can do with everything I witnessed.

I don’t consider myself an unaware person, but I was really surprised.

The sensation of taking advantage of human suffering haunts me. “Poverty tourism” is nothing new in the world, but in my career, I have never seen anything so inhuman. During the peak season, more than a thousand people visit the place every day.

A miner pokes my back and offers me a turtle made of sulfur. Once again I don’t understand anything, and Dion appears to help me. “He wants to know if you want to buy a souvenir from Ijen.” I thank him and I see that behind him is a boy pouring liquid sulfur into molds of an airplane, truck, flower, and other shapes. With that, they get extra money by selling souvenirs to tourists, at the risk of burning themselves in the liquid sulfur that keeps boiling in the bucket.

The clock strikes 5:00 in the morning. I take a deep breath and start to climb. On several occasions, we have made room for miners to overtake us. The strength they have is massive. At this moment I remember a documentary that said that the human body always finds a way to adapt to the environment. And these workers are living proof of that.

At the top of the crater, we wait for the sun to rise. The lake is covered with sulfur mist. It looks like a horror movie. A blue color fills every space as if someone has tripped over a can of paint. The fog does not dissipate and people gradually give up and begin to descend towards the parking lot. I sit and wait. I feel victorious and a failure.

I don’t need to wear the mask anymore. People continue to work as weightlifters on a championship day. At this point, a cold wind begins to push the smoke away. Within minutes a wonderful turquoise lake begins to emerge. It is amazing how such beauty can be just as toxic.

At the moment we rehearse our descent, there are few tourists left on the mountain. I start asking Dion questions while I photograph the miners organizing their stuff before they go down.

Among the miners, there are also other workers. They offer the service of transporting people. Another job created by this contradictory tourism. Using their bodies, these men are willing to carry tourists up and down the mountain, using customized and padded handcarts.

I make the descent back in silence. A miner overtakes us carrying his 90 kg of sulfur. He shifts the baskets from one shoulder to the other as if he were carrying bags of feathers. I close my eyes and a chill runs down my spine.

I allow myself to feel. I try to understand this person’s needs. The anguish that leads him to put himself in a position of extreme exhaustion. The desperation that makes him breathe a toxic gas daily. The love for the family that takes him into an active volcano. The dream of seeing their children have a better life.

Any attempt at empathy on my part should not even scratch the surface of what these people feel daily. I’m afraid.

Imagine them?

Mto bom…..sugiro uma trilha sonora: ” Viagem ao centro da terra” com o tecladista Rick Wakenam

Foi impactante, no nosso mundinho não imaginamos o que muitas pessoas passam para oferecer um pouco de dignidade a família!! Parabéns linda apresentação. Obrigado por compartilhar esse conhecimento!!